Pamela Croft’s Artistic Journey in the 1980s: The “Once We Mount the Armour” Series

Introduction: Meeting Pamela Croft

Pamela Croft is an important Australian artist who created fascinating artwork during the 1980s. From 1983 to 1988, she developed her artistic voice and created powerful pieces that explored who we are and how we protect ourselves from the world. Her most famous work, the “Once We Mount the Armour” series, used many different materials and art forms to show how people build walls around themselves for protection.

This blog will take you through Pamela’s artistic journey in the 1980s, with a special focus on her “Once We Mount the Armour” series. We’ll look at the different types of art she made, what they mean, and why her work is still important today.

Table of Contents

Early Works: Finding Her Voice (1983-1985)

When Pamela began making art in the early 1980s, she experimented with different materials to express her ideas. She worked with clay to create ceramic plaques (flat decorated pieces) and made totems by combining tree trunks with ceramic plates. She also incorporated natural materials like feathers, bark, and wattle in her sculptures, connecting her art to the natural world.

During this time, Pamela created drawings that showed her interest in identity and belonging. “Alone,” a self-portrait made with pastel crayons, gave viewers a glimpse into how she saw herself. Another drawing called “Dispossessed” (1985) used ink and pencil on paper to explore feelings of not belonging or being out of place.

These early works show that Pamela was already thinking about important questions: Who am I? Where do I belong? How do I fit into the world around me? These questions would become central to her later, more famous artwork.

The Birth of “Once We Mount the Armour” (1986-1987)

By 1986-1987, Pamela’s work had evolved into something more complex and powerful. She began creating her most important series, called “Once We Mount the Armour.” This collection of artwork used many different materials and art forms, including:

- Videos

- Live performances

- Sculptures made of bronze, ceramic, and resin

- Prints made using a special technique called lithography

- Handmade paper works

- Masks

The title “Once We Mount the Armour” is important. To “mount” armor means to put it on, like knights did long ago before battle. But Pamela wasn’t talking about real metal armor. She was talking about the emotional armor people wear to protect themselves from getting hurt.

What Did Pamela Mean by “Armour”?

Imagine you’re starting at a new school. You might act tougher or cooler than you feel because you’re scared of not fitting in. Or maybe you wear certain clothes to look like everyone else. This is a kind of “armor” – not made of metal, but made of behaviors and appearances that protect your feelings.

Pamela’s art explores this idea deeply. She wrote that armor can serve many purposes:

- “To protect the mind, soul, heart and the physical body”

- To create “emotional suits of protection, barriers against intimacy”

- To provide “disguises, allowing the ‘acting out’ of acceptable western behavior and image”

But she also discovered something important: “The suits of armour proved to be more of an emotional prison than a protection.” In other words, the walls we build to protect ourselves can turn into cages that trap us.

Pamela shared her personal experience: “By using the armours, I had learnt to hide me: my identity; my traumas; my pain; and my vulnerability to others.” Her artwork helped her understand how she had been hiding her true self behind different kinds of armor.

The Mannequin: A Powerful Symbol

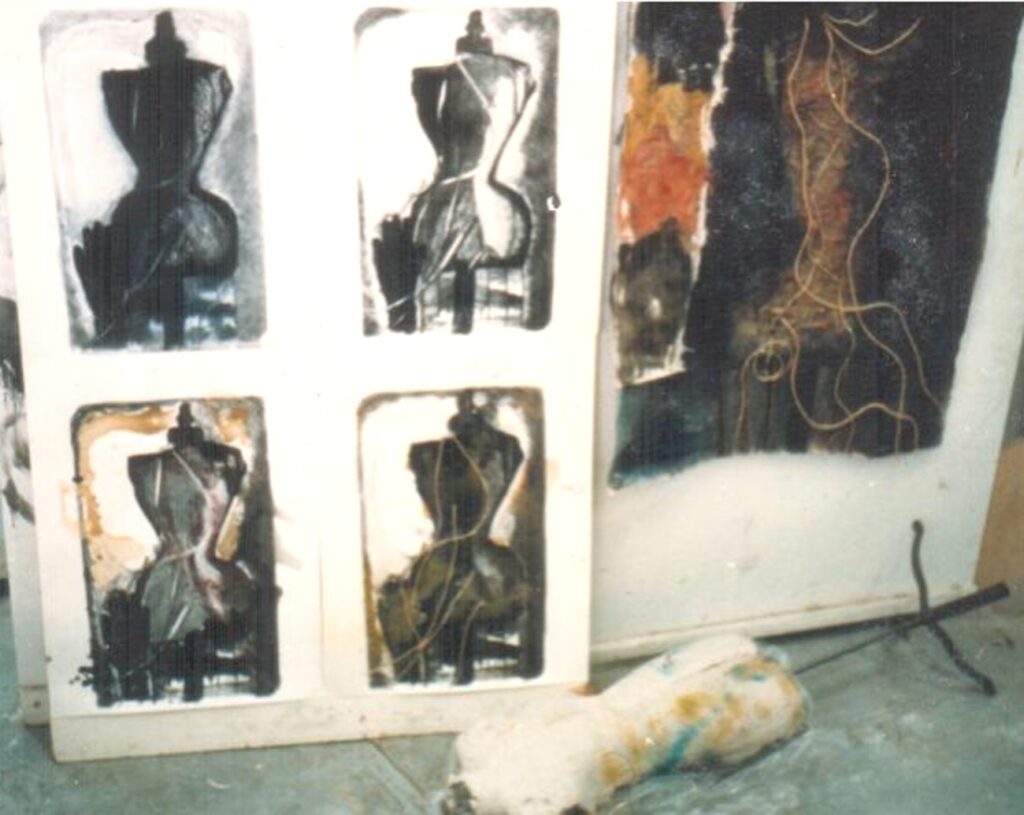

One of the most interesting parts of Pamela’s “Once We Mount the Armour” series was her use of mannequins – those human-shaped forms you see in store windows displaying clothes. She described the mannequin as an “empty vessel,” meaning it looks like a person on the outside but has nothing inside.

This made the mannequin a perfect symbol for what happens when people hide behind armor. They might look fine on the outside but feel empty or disconnected on the inside. The mannequin became a way for Pamela to show how people become “projectors of images” – like screens that show what others want to see instead of who they are.

Amazing Artworks from the “Once We Mount the Armour” Series

Let’s look at some of the specific artworks Pamela created as part of this series:

Individual Material Studies

Pamela created separate sculptures exploring each material on its own:

- “Once We Mount the Armour 1987 Bronze Sculpture”

- “Once We Mount the Armour 1987 Resin Sculpture”

- “Once We Mount the Armour 1987 Ceramic Sculpture”

The resin sculpture won First Prize at the 1988 Art to Wear Expo, showing that Pamela’s art could be worn like clothing, connecting directly to the idea of armor as something we put on.

Lithograph Prints

Pamela created a special kind of print called a lithograph. She made a series of six prints called “the Armour 1987.” These prints were shown in many different places over the years:

- Little Masters That Contemporary Artspace (Brisbane, 1987)

- Protector Spirits of My Life at Queensland Aboriginal Creations (1991)

- Whispers of Wisdom at Nona Gallery (1999)

- Subversions at Griffith University (1994)

She also created another print series called “We Can Mount the Armour 1987” using wax, gouache, oil, and pastel on paper. These were shown in exhibitions like “Gatherings” at the Brisbane Convention Centre (2001) and “No More Secrets” at Casula Powerhouse in New South Wales (1998).

Handmade Paper Mask

Pamela created a mask using paper she made herself. This was also shown at the 1988 Art to Wear Expo. Think about what a mask does – it covers your face and can change how others see you. By making the mask from handmade paper (which is delicate and can tear easily), Pamela showed how fragile our fake identities are.

Bronze, Ceramic & Resin Sculpture (1987)

One of the most important pieces combined three very different materials – bronze, ceramic, and resin. Each material tells part of the story:

- Bronze is strong and lasts a long time, like the protection we want

- Ceramic looks solid but can break easily, like our hidden vulnerability

- Resin starts as a liquid and hardens into a clear coating, like how we create artificial shells around ourselves

This sculpture was shown in exhibitions called “Duality..my story, my place” at Brutal Galerie in Brisbane (1990) and later at the Booker-Lowe Gallery in Houston, USA (2003).

Works in Progress

Interestingly, Pamela also exhibited unfinished works, like “Once We Mount the Armour 1987 Artist’s Handmade Paper Work in Progress.” She showed ceramic works before they were completely fired, letting people see the process of creating art, not just the finished product. This approach fits perfectly with her theme of revealing what’s normally hidden.

Beyond Sculpture: Performance and Video

The “Once We Mount the Armour” series wasn’t limited to physical objects. Pamela also created:

Video Works

While we don’t have many details about these videos, they were an important part of the series. Videos can show movement and change, perhaps demonstrating how people put on or take off emotional armor.

Performance Art

Pamela performed parts of “Once We Mount the Armour” at the Tropicarnival Gold Coast Festival. Performance art uses the artist’s body and actions to express ideas. By performing her exploration of armor, Pamela could show in real time how people adopt different identities and protective behaviors.

These more dynamic art forms allowed Pamela to show that armor isn’t just an object – it’s something we actively create and maintain through our behavior.

Other Important Works from the 1980s

While “Once We Mount the Armour” was Pamela’s main focus, she created other significant artworks during this time that explored similar themes:

“Resurrection”

This sculpture combined marble, brass, bronze, feathers, and bullet shells. The title suggests rebirth or coming back to life. By using bullet shells (which are connected to weapons and harm) alongside feathers (which are soft and fragile), Pamela created a powerful contrast between danger and vulnerability.

“Mother Spirit”

This collage used paperbark and feathers, natural materials that connect to the Australian landscape. The title suggests a spiritual connection to motherhood or ancestral wisdom, perhaps exploring another kind of identity beyond the artificial armor we create.

“Searching for Identity”

This work directly addressed the theme of trying to figure out who you are – a journey that many people can relate to, especially teenagers and young adults who are discovering themselves.

The Impact of Pamela’s Work

Pamela’s “Once We Mount the Armour” series was shown in many different places, from art galleries to festivals. This shows that her ideas connected with many different people. Some important places her work was exhibited include:

- Little Masters That Contemporary Artspace (Brisbane)

- Brutal Galerie (Fortitude Valley, Brisbane)

- Nona Gallery

- Griffith University

- Brisbane Convention Centre

- Booker-Lowe Gallery (Houston, USA)

- Casula Powerhouse (New South Wales)

The fact that her work traveled to Houston shows that her ideas about armor and identity spoke to people beyond Australia. This international recognition is impressive for an artist who was just establishing herself in the 1980s.

Why Pamela’s Work Still Matters Today

Even though Pamela created the “Once We Mount the Armour” series in the 1980s, her ideas are maybe even more important today. Think about how people present themselves on social media – carefully choosing the best photos, writing the perfect captions, and creating an online identity that might be very different from their real life. This is a modern form of “mounting the armour.”

Pamela’s observation that armour can become a prison is especially relevant now. Many people feel trapped by the perfect images they create online, always needing to live up to an impossible standard. Her artwork reminds us to question whether our protective layers are helping us or hurting us.

The different materials Pamela used also tell us something important: some armor looks strong but is fragile (like ceramic), while other types seem delicate but are surprisingly resilient (like handmade paper). This teaches us that strength and vulnerability aren’t always what they seem.

The Artist Behind the Armor

What makes Pamela’s exploration of armor especially powerful is that she wasn’t just observing other people – she was reflecting on her own experience. She wrote about how she had used armor to hide her identity, traumas, pain, and vulnerability from others.

This personal connection makes her artwork authentic and moving. When Pamela created mannequins wearing different types of armor, she wasn’t just making an interesting sculpture – she was exploring her emotional journey and inviting viewers to think about theirs too.

Materials and Meanings

One of the most fascinating aspects of Pamela’s work is how she used different materials to express different ideas. Here’s what some of her materials might represent:

- Bronze: Strength, permanence, traditional protection

- Ceramic: Appearing solid but fragile

- Resin: Transparency, artificial coating, manufactured protection

- Handmade paper: Personal creation, fragility, natural protection

- Feathers: Lightness, natural armor (like birds have)

- Bullet shells: Violence, extreme protection, weaponized defense

- Marble: Cold beauty, hardness, classical imagery

- Tree trunks: Rootedness, natural strength

- Bark: Protective outer layer from the natural world

By combining these materials in unexpected ways, Pamela created rich visual conversations about different types of protection and vulnerability.

Artistic Process and Evolution

Pamela’s work evolved significantly between 1983 and 1988. Her creative journey shows how an artist develops their unique voice:

- Early explorations (1983-1985): Simple materials, direct expressions of identity and displacement

- Concept development (1986): Beginning to explore the armor theme

- Full realization (1987-1988): Creating the complete “Once We Mount the Armour” series across multiple media

- Recognition and exhibition (1988 and beyond): Sharing her work with wider audiences

This evolution shows that big artistic ideas don’t usually appear overnight. They develop gradually as the artist experiments, reflects, and refines their thinking.

Lessons We Can Learn from Pamela’s Art

Pamela’s “Once We Mount the Armour” series teaches us several important lessons:

- Protection can become a prison: The walls we build to keep ourselves safe can end up cutting us off from others and from our own authentic feelings.

- Identity is complex: We all have multiple layers to who we are, and sometimes what we show the world is very different from how we feel inside.

- Materials have meaning: The physical substances we choose to express ourselves (whether in art or in what we wear) communicate messages about who we are.

- Vulnerability takes courage: Showing our true selves, with all our fears and imperfections, is difficult but necessary for real connection.

- Art can heal: By exploring her relationship with armor through art, Pamela found a way to understand and express complicated feelings about identity and protection.

Conclusion: Pamela Croft’s Lasting Impact

Pamela Croft’s journey as an artist in the 1980s shows the power of art to explore deep human experiences. Through her “Once We Mount the Armour” series, she created a visual language for understanding how we protect ourselves and what we might lose in the process.

Her work reminds us to be mindful of the armor we wear – to ask ourselves whether our protective layers are serving us well or restricting our growth and connections. By using mannequins, masks, and diverse materials, she made visible the often-invisible ways we shield ourselves from vulnerability.

What makes Pamela’s work especially valuable is how it spans from personal experience to universal human concerns. Her exploration of armor speaks to anyone who has ever hidden their true feelings, adopted a different persona to fit in, or struggled with being authentic in a sometimes-harsh world.

From performances at the Tropicarnival Festival to prize-winning sculptures at the Art to Wear Expo, from lithographs displayed in Brisbane galleries to exhibitions in Houston, Texas, Pamela Croft’s art has traveled far and connected with many different viewers. Her artistic legacy continues to remind us of the delicate balance between protection and authenticity, between the armor we mount and the vulnerability we need to truly connect with others.

As we navigate our own identities in today’s complex world, Pamela’s insights about the double-edged nature of armor remain as relevant as ever – perhaps even more so in our digital age of carefully curated images and online personas. Her art invites us to look beneath the surface, to recognize our own armor, and to consider when it might be time to set it aside.

FAQ: Pamela Croft’s “Once we mount the armour” (1983-1988)

Q1. What are the primary artistic mediums and forms explored in Pamela Croft’s portfolio “Once we mount the armour”?

Pamela Croft’s portfolio from 1983 to 1988 encompasses a diverse range of artistic mediums and forms. These include videos (“I can be your angel,” “Once we mount the armour”), performance art (Tropicarnival Gold Coast Festival), two-dimensional artworks (oil and watercolour paintings, ink and pencil drawings, pastels, gouache, lithograph and collagraph prints), and three-dimensional artworks (sculptures utilizing materials such as tree trunks, ceramic plates, feathers, bark, wattle, bamboo, wax, gauze, brass, string, wood, marble, bronze, bullet shells, sandstone, artist’s handmade paper, wool, roses, and photos).

Q2. What central concept or idea appears to drive the artistic explorations within “Once we mount the armour”?

A central concept driving Croft’s work during this period is the ambiguity surrounding the relationship between people and fashion, particularly the notions of “tribal stature and armour.” She explores how the human form and masks become sites for decoration and projection, while mannequins represent “empty vessels” embodying armour. This armour serves as a multifaceted symbol: protection for the mind, soul, heart, and physical body; emotional barriers against intimacy; and disguises for enacting socially acceptable Western behaviors and images.

Q3. How does Croft interpret the symbolic function of “armour” in her art?

For Croft, “armour” is not simply a physical covering but a complex metaphor for emotional and psychological defense mechanisms. She sees it as a way individuals attempt to protect themselves – their identity, traumas, pain, and vulnerability – from others. The mannequin, as an “empty vessel,” becomes a potent symbol of these emotional suits of protection and the barriers they create in interpersonal relationships.

Q4. According to Croft, what is the paradoxical outcome of using “suits of armour”?

Despite the initial intention of protection, Croft reflects that these “suits of armour” ultimately proved to be “more of an emotional prison than a protection.” By adopting these defenses, she learned to conceal her true self, hindering genuine connection and trapping her within the very barriers meant to safeguard her.

Q5. What is the significance of materials and techniques used in Croft’s sculptural works like “Resurrection” and the “Once we mount the armour” series?

Croft’s sculptural works demonstrate a deliberate and often unconventional use of materials. Pieces like “Resurrection” (marble, brass, bronze, feathers, bullet shells) and the various iterations of “Once we mount the armour” (bronze, ceramic, resin, artist’s handmade paper) suggest a process of assemblage and juxtaposition. The combination of natural elements (feathers, paper), industrial materials (brass, bronze, resin), and even remnants of conflict (bullet shells) likely contributes to the thematic exploration of protection, vulnerability, and identity.

Q6. How do titles like “Dispossessed,” “Alone,” and “Searching for identity” in her earlier works from 1985-1986 relate to the broader themes in “Once we mount the armour”?

These earlier titles offer insight into the personal and emotional landscape that informs the later “armour” series. Themes of displacement (“Dispossessed”), isolation (“Alone”), and the quest for self-understanding (“Searching for identity”) suggest a pre-existing vulnerability and perhaps a need for the kind of protection symbolized by the armour. These works lay the groundwork for the exploration of how individuals construct and inhabit protective facades.

Q7. What does Croft’s mention of disguises and “acting out’ of acceptable western behaviour” imply about her observations of identity and culture?

This statement suggests Croft is critically examining the pressures to conform to dominant Western societal norms. The idea of disguises and “acting out” implies a performative aspect to identity, particularly for non-Aboriginal peoples (as indicated in the preceding sentence in the source). The “armour” then becomes not just a personal defense but also a means of navigating and potentially concealing one’s true self within a specific cultural context.

Q8. How does the inclusion of exhibition history contribute to understanding the significance of “Once we mount the armour”?

The extensive list of exhibitions, including “Art Bilong Tudei,” “The National Aboriginal Art Award,” and “You came to my country and didn’t turn black,” alongside galleries like Queensland Aboriginal Creations and Kung Gubunga Dreamtime Gallery, highlights the recognition and diverse contexts in which Croft’s work was shown. The inclusion in Aboriginal art-focused exhibitions suggests her work may also engage with themes of Indigenous identity and experience, while broader art awards and gallery shows indicate a wider artistic resonance with the themes of protection, identity, and societal pressures explored in “Once we mount the armour.”